Recent news concerning the use of corn waste or residual products to create commercially viable ethanol reminds me of a game of checkers. One jump forward, one jump backward, one move sideways. Depending how smart, bored or prone to crying the players are, the game often results in either a stalemate or a glorious victory, particularly glorious when it’s your grandson or granddaughter.

The good news! The American-owned POET and the Dutch-owned Royal DSM opened the first facility in Iowa that produces cellulosic ethanol from corn waste (not your favorite corn on the cob), only the second in the U.S. to commercially produce cellulosic ethanol from agricultural waste, according to James Stafford’s recent article in OilPrice.com (Sept. 5).

The new owners jumped (note the analogy to checkers…my readers are bright) with joy. They announced, perhaps, a bit prematurely, that the joint project, called Project LIBERTY, is the “first step in transforming our economy, our environment and our national security.” After their press release, quick, generally positive, comments came from electric and hydrogen fuel makers, CNG producers, advocates of natural gas-based ethanol and a whole host of other replacement fuel enthusiasts. The comments reflected the high hopes and dreams of leaders of public interest groups, some in the business community, several think tanks and many in the government who see transitional replacement fuels reducing U.S. dependency on oil and simultaneously improving the economy and environment. Several were fuel agnostic as long as increased competition at the pump offered a range of fuels at lower costs to consumers and reduced environmental harm to the nation.

Ethanol from corn waste, if the conversion could be made easily and if it resulted in less costs than gasoline, would mute tension between those who argue that use of corn for ethanol would limit food supplies and provide consumers a good deal, cost wise. The cowboys and the farmers might even eat the same table. (Sorry, Mr. Hammerstein.)

Life is never easy. Generally, when a replacement fuel seems to offer competition to gasoline, the API (American Petroleum Institute — supported by the oil industry) immediately tries to check the advocates of replacement fuel. The association didn’t disappoint. It made a clever jump of its own with a confusing move…sort of a bait and switch move.

API’s check and jump is reflected in their quote to Scientific American. It indicated, in holier-than-thou tones, “API supports the use of advanced biofuels, including cellulosic biofuels, once they are commercially viable and in demand by consumers. But EPA must end mandates for these fuels that don’t even exist.” Wow, how subtle. API supports and then denies!

What a bunch of hokum! Given their back-handed endorsement of advanced biofuels, would API and its supporters among oil companies agree to end their unneeded government tax subsidies simultaneously with EPA’s reductions or ending of mandates? Would API and its supporters agree to add provisions to franchise agreements that would allow gas station owners or managers to locate ethanol from cellulosic biofuels in a central visible pump? Would API work with advocates of replacement fuels to open up the gas market to replacement fuels and competition? Would API agree to a collaborative study of the impact of corn-based residue as the primers of ethanol with supporters of residue derived ethanol, a study including refereed, independent evaluators, and abide by the results? If you answer no to all of these questions, you would be right. API, in effect, is clearly trying to jump supporters of corn-based residual ethanol and block them from producing and marketing their product. Conversely, if you believe the answer is yes to one or more of the questions, you will wait a long time for anything to happen and I will offer to sell you the Golden Gate Bridge and more.

The advocates and producers of cellulosic-based ethanol from corn waste (next move) were suggested by overheard advisors to API. These advisors from the oil industry cheered API’s last move and noted that a recent study in Nature Climate Change, a respected peer-reviewed journal, suggested that biofuels made from corn residue emit 7 percent more greenhouse gases in early years than gasoline and does not meet current energy laws. They wanted checkerboard pieces held by advocates of corn residue off the policy board.

Oh, but the supporters are wise! They don’t give in right away. They pointed to an EPA analysis which indicates that using corn residue to secure ethanol meets existing energy laws and probably produces much, much less carbon than gasoline. Studies like the one reported in Nature Climate Change do not, according to an EPA spokesperson, report on lifecycle changes in an adequate way — from pre-planting, through production, blending, distribution, retailing produce and use. Moreover, a recent analysis funded by DuPont — soon to open a new cellulosic residue to ethanol facility — indicates that using corn residue to produce ethanol will be 100 percent better than gasoline, concerning GHG emissions. (Supporters were a bit hesitant about shouting out DuPont’s involvement in funding the study. It is a chemical company with a mixed environmental record. But after review, supporters indicated it seemed like a decent analysis.)

The response of supporters and its intensity caused API and its advisors to withdraw their insistence, that the checkers of the advocates of corn based residue derived ethanol come of the board. Instead, they asked for a two-hour break in the game. The residue folks were scared. “API was a devious group. What were they up too?”

When the game started again, both supporters and opponents pulled out lots of competing studies, before they made their moves. The only things they agreed on was that the extent of land use devoted to corn, combined with the way farmers manage the soil and the residue, likely would significantly affect GHG emissions. Keeping a strategic amount of residual on the soil would help reduce emissions.

Supporters of corn-based residue argued for a quick collaborative study that might help bridge the analysis gap. But they wanted a bonafide commitment from API that if corn-based residual, derived ethanol, proved better than gasoline, it would support it as a transitional replacement fuel. No soap! The game ended in a stalemate.

Based on talking to experts and surveying much of the literature, I believe that the fictional checkers game tilts toward corn residual derived ethanol, assuming significant attention is granted by farmers to management of the soil and the residue. Whether corn residual-based ethanol becomes competitive as a transitional replacement fuel will be based mostly on farmer intelligence, consumer and political acceptance and a set of even playing field regulations. It, as well as natural gas-based ethanol, as I have written in previous columns, are worthy of a set of demonstration efforts. The nation will have an extended wait until electric and hybrid cars make a big dent regarding the share of the total number of cars in America. We have a moral obligation to do the best we know how to do to lower GHG emissions and other pollutants. We shouldn’t let the almost perfect in our future reduce the possible good now.

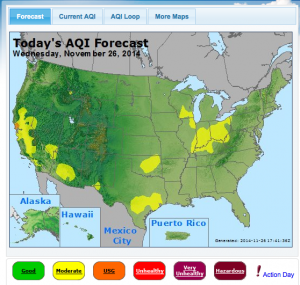

(Click on the image at right to check the national Air Quality Index.)

(Click on the image at right to check the national Air Quality Index.)