Fake and real news: Links between GHG reduction and alternative fuels

Turn on your local news every night and you’ll need a sleeping pill to get some rest. The format and content is the same around the country: a lot of tragic crime — ranging from sexual harassment, robbery and shootings — for about ten minutes; local sports for about 5 minutes; what seems like ten minutes of intermittent advertising; silly banter between two or more anchors for two minutes; and a human-interest story to supposedly lighten up your day at the very end of the show — likely about a dog and cat who have learned to dance together or a two-year-old child who already knows how to play Mozart. You get the picture!

Turn on your local news every night and you’ll need a sleeping pill to get some rest. The format and content is the same around the country: a lot of tragic crime — ranging from sexual harassment, robbery and shootings — for about ten minutes; local sports for about 5 minutes; what seems like ten minutes of intermittent advertising; silly banter between two or more anchors for two minutes; and a human-interest story to supposedly lighten up your day at the very end of the show — likely about a dog and cat who have learned to dance together or a two-year-old child who already knows how to play Mozart. You get the picture!

Local news, as presently structured, is not about to send you to sleep feeling good about humanity, never mind your community or nation. National news is really only marginally better. Again, the first ten minutes, more often than not, are about environmental disasters in the nation or the world — hurricanes, volcanoes, cyclones and tornadoes. The second ten minutes includes maybe one or two tragically laced stories, more often than not, about fleeing refugees, suicide bombings, dope and dopes and conflict. Finally, at the end of the program, for less than a minute or two, there is generally a positive portrayal of a 95-year-old marathon runner or a self-made millionaire who is now single-handedly funding vaccinations for kids in Transylvania after inventing a three-wheeled car that will never need refueling and can seat twenty-five people.

Maybe this is how the world is! We certainly need to think about the problems and dangers faced by our communities, the nation and its citizens. Every now and then, Americans complain about the media’s emphasis on bad news. But their complaints are rarely recorded precisely in surveys of viewership. We criticize the primary emphasis on bad news, but seem to watch it more than good news. Somewhat like football, we know it causes emotional and physical injuries to players, but support it with the highest TV ratings and attendance numbers.

Jimmy Fallon, responding to the visible (but likely surface) cry for more good news, has added a section to The Tonight Show. He delivers fake, humorous news, which is, at times, an antidote to typical TV or cable news shows. Perhaps John Oliver, a rising comedian on HBO, does it even better. He takes real, serious news about human and institutional behavior that hurts the commonweal and makes us laugh. In the process, we gain insight.

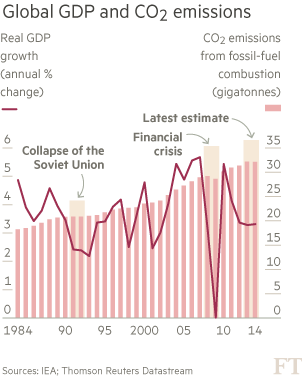

This week’s news about carbon dioxide emissions “stalling” in 2014 for the first time in 40 years appeared in most newspapers (I am a newspaper junkie) led by The New York Times and the Financial Times. It seemed like good news! Heck, while the numbers don’t reflect a decline in carbon emissions, neither do they illustrate an increase. Let’s be thankful for what we got over a two-year period (in the words of scientists — stability, or 32.3bn tons a year).

But don’t submit the carbon stability numbers to Jimmy Fallon just yet. It’s much too early for a proposed new segment on The Tonight Show called “Real as Opposed to Fake, Good News.” Too much hype could convince supporters of efforts to slow down climate change that real progress is being made. We don’t know yet. Recent numbers only reflect no carbon growth from the previous year over a 12-month period. The numbers might be only temporary. They shouldnt lessen the pressure to define a meaningful fair and efficient strategy to lower GHG. If this occurs, yesterday’s good news will become a real policy and environmental problem for the U.S. and the world for many, many tomorrows.

I am concerned that the stability shown in the carbon figures may be related to factors that might be short lived. Economists and the media have attributed the 2014 plateau to decreases in the rate of growth of China’s energy consumption and new government policies, as well as regulations on economic growth in many nations (e.g., requirements for more energy-efficient buildings and the production of more fuel-efficient vehicles), the growth of the renewable energy sector and a shift to natural gas by utilities.

Truth be told, no one appears to have completed a solid factor analysis just yet. We don’t really know whether what occurred is the beginning of a continuous GHG emission slowdown and a possible important annual decrease.

Many expert commentators hailed the IEA’s finding, including its soon-to-be new director, Dr. Fatih Birol. He indicated that this is “a very welcome surprise…for the first time, greenhouse gas emissions are decoupling from economic growth.”

Yet, most expert commentators suggest we should be careful. They noted that the data, while positive, is insufficient to put all our money on a bet concerning future trends. For example, Hal Harvey, head of Energy Innovation, indicated, “one year does not a trend make.”

Many articles responding to the publication of the “carbon stall” story, either implicitly or explicitly, suggested that to sustain stability and move toward a significant downward trend requires a national, comprehensive strategy that includes the transportation sector. It accounts for approximately 17 percent of all emissions, probably higher, since other categories such as energy use, agriculture and land use have murky boundaries with respect to content. Indeed, a growing number of respected environmental leaders and policy analysts now include vehicle emissions as well as emissions from gasoline production and distribution as a “must lower” part of a needed comprehensive national, state and local set of emission reduction initiatives, particularly,if the nation is to meet temperature targets. Further, there is an admission that is becoming almost pervasive: that renewable fuels and renewable fuel powered vehicles, while supported by most of us, are not yet ready for prime time.

While ethanol, methanol and biofuels are not without criticism as fuels, they and other alternative fuels are better than gasoline with respect to emissions. For example, the GREET Model used by the federal government indicates that ethanol (E85) emits 22.4 percent less GHG emissions (grams per mile) when compared to gasoline (E10). The calculation is based on life-cycle data. Other independent studies show similar results, some a higher, others a lower percent in reductions. But the important point is that there is increased awareness that alternative fuels can play a role in the effort to tamp down GHG.

So why, at times, are some environmentalists and advocates of alternative fuels at loggerheads. I suspect that it relates to the difference between perfectibility and perfection. Apart from those in the oil industry who have a profit at stake in oil and welcome their almost-monopoly status concerning retail sales of gasoline, those who fear alternatives fuels point to the fact that they still generate GHG emissions and the assumption, that, if they become competitive, there will be less investment in research and development of renewables. Yes! Alternative fuels are not 100 percent free of emissions. No! Investment in renewables will remain significant, assuming that the American history of innovation and investment in transportation is a precursor of the future.

Putting America on the path to significant emission reduction demands a strong coalition between environmentalists and alternative fuel advocates. Commitments need to be made by public, private and nonprofit sectors to work together to implement a realistic comprehensive fuel policy; one that views alternative fuels as a transitional and replacement fuel for vehicles and that encompasses both alternative fuels and renewables. Two side of the same policy and behavior coin. President Franklin Roosevelt, speaking about the travails of the depression, once said, “All we have to fear is fear itself.” His words fit supporters of both alternative fuels and renewables. Let’s make love, not war!