America’s oil imports are higher than you think

It seems like every day there’s a new headline about the dominance of America’s petroleum sector. Read more →

It seems like every day there’s a new headline about the dominance of America’s petroleum sector. Read more →

For nearly a decade now, most gasoline sold in the U.S. has contained 10 percent ethanol. This allowed us to do away with toxic additives like BTEX and reduce our dependence on foreign oil.

So we’re dependent on foreign oil. How bad could that be?

We’re producing more crude and our cars are more efficient, yet we still import millions of barrels of foreign oil per day. What’s going on?

The Greeks are going broke…slowly! The Russians are bipolar with respect to Ukraine! Rudy Giuliani has asked the columnist Ann Landers (she was once a distant relative of the author) about the meaning of love! President Obama, understandably, finds more pleasure in the holes on a golf course than the deep political holes he must jump over in governing, given the absence of bipartisanship.

But there is good news! Many ethanol producers and advocacy groups, with enough love for America to encompass this past Valentine’s Day and the next (and of course, with concern for profits), have acknowledged that a vibrant, vigorous, loving market for E85 is possible, if E85 costs are at least 20 percent below E10 (regular gasoline) — a percentage necessary to accommodate the fact that E10 gas gets more mileage per gallon than E85. Consumers may soon have a choice at more than a few pumps.

But there is good news! Many ethanol producers and advocacy groups, with enough love for America to encompass this past Valentine’s Day and the next (and of course, with concern for profits), have acknowledged that a vibrant, vigorous, loving market for E85 is possible, if E85 costs are at least 20 percent below E10 (regular gasoline) — a percentage necessary to accommodate the fact that E10 gas gets more mileage per gallon than E85. Consumers may soon have a choice at more than a few pumps.

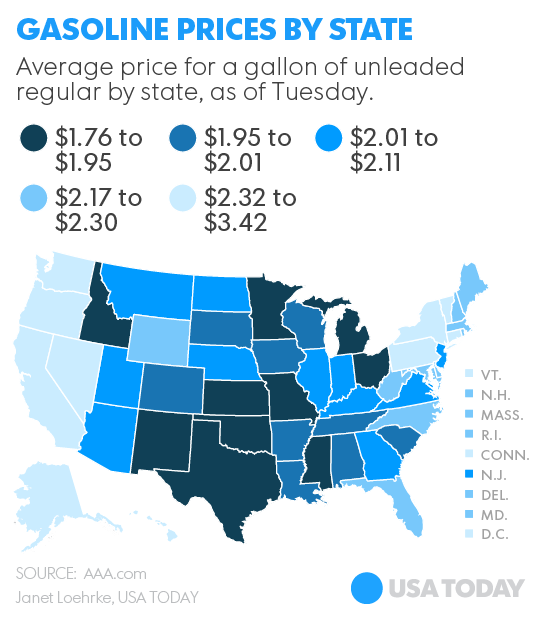

In recent years, the E85 supply chain has been able to come close, in many states, to a competitive cost differential with respect to E10. Indeed, in some states, particularly states with an abundance of corn (for now, ethanol’s principal feedstock), have come close to or exceeded market-based required price differentials. Current low gas prices resulting from the decline of oil costs per barrel have thrown price comparisons between E85 and E10 through a bit of a loop. But the likelihood is that oil and gasoline prices will rise over the next year or two because of cutbacks in the rate of growth of production, tension in the Middle East, growth of consumer demand and changes in currency value. Assuming supply and demand factors follow historical patterns and government policies concerning, the use of RNS credits and blending requirements regarding ethanol are not changed significantly, E85 should become more competitive on paper at least pricewise with gasoline.

Ah! But life is not always easy for diverse ethanol fuel providers — particularly those who yearn to increase production so E85 can go head-to-head with E10 gasoline. Maybe we can help them.

Psychiatrists, sociologists and poll purveyors have not yet subjected us to their profound articles concerning the possible effect of low gas prices on consumers, particularly low-income consumers. Maybe, just maybe, a first-time, large grass-roots consumer-based group composed of citizens who love America will arise from the good vibes and better household budgets caused by lower gas prices. Maybe, just maybe, they will ask continuous questions of their congresspersons, who also love America, querying why fuel prices have to return to the old gasoline-based normal. Similarly, aided by their friendly and smart economists, maybe, just maybe, they will be able to provide data and analysis to show that if alternative lower-cost based fuels compete on an even playing field with gasoline and substitute for gasoline in increasing amounts, fuel prices at the pump will likely reflect a new lower-cost based normal favorable to consumers. It’s time to recognize that weakening the oil industry’s monopolistic conditions now governing the fuel market would go a long way toward facilitating competition and lowering prices for both gasoline and alternative fuels. It, along with some certainty concerning the future of the renewable fuels program, would also stimulate investor interest in sorely needed new fuel stations that would facilitate easier consumer access to ethanol.

Who is for an effective Open Fuel Standard Program? People who love America! It’s the American way! Competition, not greed, is good! Given the oil industry’s ability to significantly influence, if not dominate, the fuel market, it isn’t fair (and maybe even legal) for oil companies to legally require franchisees to sell only their brand of gasoline at the pump or to put onerous requirements on the franchisees should they want to add an E85 pump or even an electric charger. It is also not right (or likely legal) for an oil company and or franchisee to put an arbitrarily high price on E85 in order to drive (excuse the pun) consumers to lower priced gasoline?

Although price is the key barrier, now affecting the competition between E85 and E10, it is not the only one. In this context, ethanol’s supply chain participants, including corn growers, and (hopefully soon) natural gas providers, need to review alternate, efficient and cost-effective ways to produce, blend, distribute and sell their product. More integration, cognizant of competitive price points and consistent with present laws and regulations, including environmental laws and regulations, is important.

The ethanol industry and its supporters have done only a fair to middling job of responding to the oil folks and their supporters who claim that E15 will hurt automobile engines and E85 may negatively affect newer FFVs and older internal combustion engines converted to FFVs. Further, their marketing programs and the marketing programs of flex-fuel advocates have not focused clearly on the benefits of ethanol beyond price. Ethanol is not a perfect fuel but, on most public policy scales, it is better than gasoline. It reflects environmental, economic and security benefits, such as reduced pollutants and GHG emissions, reduced dependency on foreign oil and increased job potential. They are worth touting in a well-thought-out, comprehensive marketing initiative, without the need to use hyperbole.

America and Americans have done well when monopolistic conditions in industrial sectors have lessened or have been ended by law or practice (e.g., food, airlines, communication, etc.). If you love America, don’t leave the transportation and fuel sector to the whims and opportunity costing of the oil industry.

Some environmentalists believe that if you invest in and develop alternative replacement fuels (e.g., ethanol, methanol, natural gas, etc.) innovation and investment with respect to the development of fuel from renewables will diminish significantly. They believe it will take much longer to secure a sustainable environment for America.

Some environmentalists believe that if you invest in and develop alternative replacement fuels (e.g., ethanol, methanol, natural gas, etc.) innovation and investment with respect to the development of fuel from renewables will diminish significantly. They believe it will take much longer to secure a sustainable environment for America.

Some of my best friends are environmentalists. Most times, I share their views. I clearly share their views about the negative impact of gasoline on the environment and GHG emissions.

I am proud of my environmental credentials and my best friends. But fair is fair — there is historical and current evidence that environmental critics are often using hyperbole and exaggeration inimical to the public interest. At this juncture in the nation’s history, the development of a comprehensive strategy linking increased use of alternative replacement fuels to the development and increased use of renewables is feasible and of critical importance to the quality of the environment, the incomes of the consumer, the economy of the nation, and reduced dependence on imported oil.

There you go again say the critics. Where’s the beef? And is it kosher?

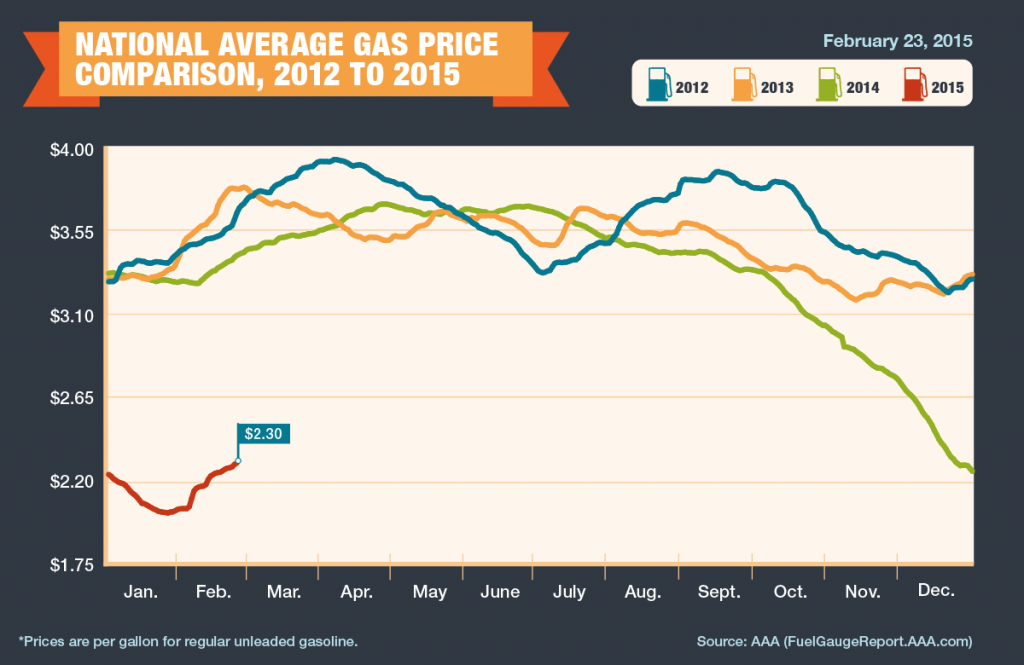

Gasoline prices are at their lowest in years. Today’s prices convert gasoline — based on prices six months ago, a year ago, two years ago — into, in effect, what many call a new product. But is it akin to the results of a disruptive technology? Gas at $3 to near $5 a gallon is different, particularly for those who live at the margin in society. Yet, while there are anecdotes suggesting that low gas prices have muted incentives and desire for alternative fuels, the phenomena will likely be temporary. Evidence indicates that new ethanol producers (e.g., corn growers who have begun to blend their products or ethanol producers who sell directly to retailers) have entered the market, hoping to keep ethanol costs visibly below gasoline. Other blenders appear to be using a new concoction of gasoline — assumedly free of chemical supplements and cheaper than conventional gasoline — to lower the cost of ethanol blends like E85.

Perhaps as important, apparently many ethanol producers, blenders and suppliers view the decline in gas prices as temporary. Getting used to low prices at the gas pump, some surmise, will drive the popularity of alternative replacement fuels as soon as gasoline, as is likely, begins the return to higher prices. Smart investors (who have some staying power), using a version of Pascal’s religious bet, will consider sticking with replacement fuels and will push to open up local, gas-only markets. The odds seem reasonable.

Now amidst the falling price of gasoline, General Motors did something many experts would not have predicted recently. Despite gas being at under $2 in many areas of the nation and still continuing to decrease, GM, with a flourish, announced plans, according to EPIC (Energy Policy Information Agency), to “release its first mass-market battery electric vehicle. The Chevy Bolt…will have a reported 200 mile range and a purchase price that is over $10,000 below the current asking price of the Volt.It will be about $30,000 after federal EV tax incentives. Historically, although they were often startups, the recent behavior of General Motor concerning electric vehicles was reflected in the early pharmaceutical industry, in the medical device industry, and yes, even in the automobile industry etc.

GM’s Bolt is the company’s biggest bet on electric innovation to date. To get to the Bolt, GM researched Tesla and made a $240 million investment in one of its transmissions plan.

Maybe not as media visible as GM’s announcement, Blume Distillation LLC just doubled its Series B capitalization with a million-dollar capital infusion from a clean tech seed and venture capital fund. Tom Harvey, its vice president, indicated Blume’s Distillation system can be flexibly designed and sized to feedstock availability, anywhere from 250,000 gallons per year to 5 MMgy. According to Harvey, the system is focused on carbohydrate and sugar waste streams from bottling plants, food processors and organic streams from landfill operations, as well as purpose-grown crops.

The relatively rapid fall in gas prices does not mean the end of efforts to increase use of alternative replacement fuels or renewables. Price declines are not to be confused with disruptive technology. Despite perceptions, no real changes in product occurred. Gas is still basically gas. The change in prices relates to the increased production capacity generated by fracking, falling global and U.S. demand, the increasing value of the dollar, the desire of the Saudis to secure increased market share and the assumed unwillingness of U.S. producers to give up market share.

Investment and innovation will continue with respect to alcohol-based alternative replacement and renewable fuels. Increasing research in and development of both should be part of an energetic public and private sector’s response to the need for a new coordinated fuel strategy. Making them compete in a win-lose situation is unnecessary. Indeed, the recent expanded realization by environmentalists critical of alternative replacement fuels that the choices are not “either/or” but are “when/how much/by whom,” suggesting the creation of a broad coalition of environmental, business and public sector leaders concerned with improving the environment, America’s security and the economy. The new coalition would be buttressed by the fact that Americans, now getting used to low gas prices, will, when prices rise (as they will), look at cheaper alternative replacement fuels more favorably than in the past, and may provide increasing political support for an even playing field in the marketplace and within Congress. It would also be buttressed by the fact that increasing numbers of Americans understand that waiting for renewable fuels able to meet broad market appeal and an array of household incomes could be a long wait and could negatively affect national objectives concerning the health and well-being of all Americans. Even if renewable fuels significantly expand their market penetration, their impact will be marginal, in light of the numbers of older internal combustion cars now in existence. Let’s move beyond a win-lose “muddling through” set of inconsistent policies and behavior concerning alternative replacement fuels and renewables and develop an overall coordinated approach linking the two. Isaiah was not an environmentalist, a businessman nor an academic. But his admonition to us all to come and reason together stands tall today.

President Obama touched on several aspects of the energy debate during Tuesday night’s State of the Union Address, including:

Imported oil:

More of our kids are graduating than ever before; more of our people are insured than ever before; we are as free from the grip of foreign oil as we’ve been in almost 30 years.

Ramped-up U.S. oil production:

At this moment — with a growing economy, shrinking deficits, bustling industry, and booming energy production — we have risen from recession freer to write our own future than any other nation on Earth.

Consumers savings from cheap gasoline:

We believed we could reduce our dependence on foreign oil and protect our planet. And today, America is number one in oil and gas. America is number one in wind power. Every three weeks, we bring online as much solar power as we did in all of 2008. And thanks to lower gas prices and higher fuel standards, the typical family this year should save $750 at the pump.

The debate over the TransCanada Keystone XL pipeline:

21st century businesses need 21st century infrastructure — modern ports, stronger bridges, faster trains and the fastest internet. Democrats and Republicans used to agree on this. So let’s set our sights higher than a single oil pipeline. Let’s pass a bipartisan infrastructure plan that could create more than thirty times as many jobs per year, and make this country stronger for decades to come.

And something else about solar power:

I want Americans to win the race for the kinds of discoveries that unleash new jobs — converting sunlight into liquid fuel …

As The New Republic noted, it was the first time in his six SOTU Addresses that Obama mentioned Keystone:

It’s not surprising he’d weigh in now, given how Keystone has dominated the first few weeks of debate in the new Republican Congress. Lately, Obama has sounded skeptical of the pipeline’s economic benefits, but we still don’t have many clues as to how he will decide Keystone’s final fate in coming months.

(Photo: WhiteHouse.gov)

“It’s a puzzlement,” said the King to Anna in “The King and I,” one of my favorite musicals, particularly when Yul Brynner was the King. It is reasonable to assume, in light of the lack of agreement among experts, that the Chief Economic Adviser to President Obama and the head of the Federal Reserve Bank could well copy the King’s frustrated words when asked by the president to interpret the impact that the fall in oil and gasoline prices has on “weaning the nation from oil” and on the U.S. economy. It certainly is a puzzlement!

What we believe now may not be what we know or think we know in even the near future. In this context, experts are sometimes those who opine about economic measurements the day after they happen. When they make predictions or guesses about the behavior and likely cause and effect relationships about the future economy, past experience suggests they risk significant errors and the loss or downgrading of their reputations. As Walter Cronkite used to say, “And that’s the way it is” and will be (my addition).

So here is the way it is and might be:

1. The GDP grew at a healthy rate of 3.5 percent in the third quarter, related in part to increased government spending (mostly military), the reduction of imports (including oil) and the growth of net exports and a modest increase in consumer spending.

2. Gasoline prices per gallon at the pump and per barrel oil prices have trended downward significantly. Gasoline now hovers just below $3 a gallon, the lowest price in four years. Oil prices average around $80 a barrel, decreasing by near 25 percent since June. The decline in prices of both gasoline and oil reflects the glut of oil worldwide, increased U.S. oil production, falling demand for gasoline and oil, and the likely desire of exporting nations (particularly in the Middle East) to protect global market share.

Okay, what do these numbers add up to? I don’t know precisely and neither do many so-called experts. Some have indicated that oil and gas prices at the pump will continue to fall to well under $80 per barrel, generating a decline in the production of new wells because of an increasingly unfavorable balance between costs of drilling and price of gasoline. They don’t see pressure on the demand side coming soon as EU nations and China’s economies either stagnate or slow down considerably and U.S. economic growth stays below 3 percent annually.

Other experts (do you get a diploma for being an expert?), indicate that gas and oil prices will increase soon. They assume increased tension in the Middle East, the continued friction between the West and Russia, the change of heart of the Saudis as well as OPEC concerning support of policies to limit production (from no support at the present time, to support) and a more robust U.S. economy combined with a relaxation of exports as well as improved consumer demand for gasoline,

Nothing, as the old adage suggests, is certain but death and taxes. Knowledge of economic trends and correlations combined with assumptions concerning cause and effect relationships rarely add up to much beyond clairvoyance with respect to predictions. Even Nostradamus had his problems.

If I had to place a bet I would tilt toward gas and oil prices rising again relatively soon, but it is only a tilt and I wouldn’t put a lot of money on the table. I do believe the Saudis and OPEC will move to put a cap on production and try to increase prices in the relatively near future. They plainly need the revenue. They will risk losing market share. Russia’s oil production will move downward because of lack of drilling materials and capital generated by western sanctions. The U.S. economy has shown resilience and growth…perhaps not as robust as we would like, but growth just the same. While current low gas prices may temporarily impede sales of electric cars and replacement fuels, the future for replacement fuels, such as ethanol, in general looks reasonable, if the gap between gas prices and E85 remains over 20 percent — a percentage that will lead to increased use of E85. Estimates of larger cost differentials between electric cars, natural gas and cellulosic-based ethanol based on technological innovations and gasoline suggest an extremely competitive fuel market with larger market shares allocated to gasoline alternatives. This outcome depends on the weakening or end of monopolistic oil company franchise agreements limiting the sale of replacement fuels, capital investment in blenders and infrastructure and cheaper production and distribution costs for replacement fuels. Competition, if my tilt is correct, will offer lower fuel prices to consumers, and probably lend a degree of stability to fuel markets as well as provide a cleaner environment with less greenhouse gas emissions. It will buy time until renewables provide a significant percentage of in-use automobiles and overall demand.

Rereading Alfred North Whitehead, one of my favorite philosophers, provides the context for the current debate over the wisdom of using the EPA’s amended transportation emissions model (Motor Vehicle Emission Simulator, or MOVES) for state-by-state analysis. He once indicated that, “There are no whole truths; all truths are half-truths. It is trying to treat them as whole truths that plays the devil.”

I am uncertain about Whitehead’s skepticism, if treated as an absolute. However, it does give pause when judging the use of an amended MOVES model, based mostly on advocacy research by the nonprofit group, the Coordinating Research Council (CRC). The CRC is funded by the oil industry, through the American Petroleum Institute (API), and auto manufacturers.

CRC was tasked by the EPA with amending MOVES and applying it to measure and determine the impact of vehicular emissions. The model and related CRC analysis was subject to comments in the Federal Register but the structure of the Register mutes easy dialogue over tough, but important, methodological disagreements among experts. Apparently, no refereed panel subjected the CRC’s process or product to critique before the EPA granted both its imperator and sent it out to the states for their use.

I am concerned that if the critics are correct, premature statewide use of the amended MOVES model will mistakenly impede development and use of alternative transitional fuels to replace gasoline, particularly ethanol, and negatively influence related federal, state and local policies and programs concerning the same. If this occurs, because of apparent mistakes in the model (and the data plugged into it), the road to significant use of renewable fuels in the future will be paved with higher costs for consumers, higher levels of pollutants and higher GHG emissions.

With some exceptions, the EPA has been a strong supporter of unbiased, nonpartisan research. Gina McCarthy, its present leader, is an outstanding administrator, like many of her predecessors, like Douglas Costle (I am proud to say that Doug worked with me on urban policy, way, way back in the sixties), Russell Train, Carol Browner, William Reilly, Christine Todd Whitman, Bill Ruckelshaus and Lee Thomas. No axes to grind; no ideological or client bias…only a commitment to help improve the environment for the American people. I feel comfortable that she will listen to the critics of MOVES.

The amended MOVES may well be the best thing since the invention of Swiss cheese. It could well help the nation, its states and its citizens determine the truths or even half-truths (that acknowledge uncertainties) related to gasoline use and alternative replacement fuels. But why the hurry in making it the gold standard for emission and pollutant analysis at the state or, indeed, the federal level, in light of some of the perceived methodological and participatory problems?

Some history! Relatively recently, the EPA correctly criticized CRC because of its uneven (at best) analytical approach to reviewing the effect of E15 on car engines. Paraphrasing the EPA’s conclusions, the published CRC study reflected a bad sample as well as too small a sample. Its findings, indicating that E15 had an almost uniform negative impact on internal combustion engines didn’t comport with facts.

The CRC’s study of E15 was, pure and simple, advocacy research. CRC reports generally reflect the views of its oil and auto industry funders and results can be predicted early on before their analytical efforts are completed. Some of its reports are better than others. But overall, it is not known for independent unbiased research.

The EPA’s desire for stakeholder involvement in up grading and use of MOVES to measure emissions is laudable. However it seems that the CRC was the primary stakeholder involved on a sustained basis in the effort. No representatives of the replacement fuel industry, no nonpartisan independent nonprofit think tanks, no government-sponsored research groups and no business or environmental advocacy groups were apparently included in the effort. Given the cast of characters (or the lack thereof) in the MOVES’ update, there’s little wonder that the CRC’s approach and subsequently the EPA’s efforts to encourage states to use the amended model have been and, I bet, will be heavily criticized in the months ahead.

Two major, well-respected national energy and environmental organizations, Energy Future Coalition (EFC) and Urban Air Initiative, have asked the EPA to immediately suspend the use of the MOVES with respect to ethanol blends. Both want the CRC/MOVES study and model to be peer reviewed by experts at Oak Ridge National Lab (ORNL), and the National Renewable Energy Lab (NREL). I would add the Argonne National Laboratory because of its role in administering GREET, The Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Transportation Model. Further, both implicitly argue that Congress should not use the CRC study and MOVES until the data and methodological issues are fixed. Indeed, before policy concerning the use of alternative replacement fuels is debated by the administration, Congress and the states both appear to want to be certain that MOVES is able to provide reasonably accurate estimates of emissions and market-related measurements, particularly with respect to ethanol and, as Whitehead would probably say, at least provide half-truths, or, as Dragnet’s Detective Jack Webb often said, “Just the facts, ma’am,” or at least just the half-truths, nothing but at least the half-truths.

What are the key issues upsetting the critics like the EFC and the Urban Air Initiative? Apart from the pedigree of the CRC and the de minimis roles granted other stakeholders than the oil industry, the CRC/MOVES model, reflects match blending instead of splash blending to develop ethanol/gasoline blends. Sounds like two different recipes with different products — and it is. Splash blending is used in most vehicles in the U.S. and generally is perceived as producing less pollution.

Let’s skip the precise formula. It’s complicated and more than you want to know. Just know that according to the letter sent to the EPA by the EFC and Urban Air Quality on Oct. 20th, the use of match blending requires higher boiling points for distillation, and these points, in turn are generally the worst polluting aromatic parts of gasoline. It noted that match blending, as prescribed by the MOVES, results in blaming ethanol for increased emissions rather than the base fuel. There is no regulatory, mechanical or health justification for adding high boiling point hydrocarbons to test fuels for purposes of measuring changes in vehicle tailpipe emissions, when ethanol is part of the fuel mixture. Independent investigations by automakers and other fuel experts confirm that the use of match blending in the study mistakenly attributed increased emission levels to ethanol rather than to the addition of aromatics and other high boiling hydrocarbons, thereby significantly distorting the model’s emission results. A peer-reviewed analysis, which will be published shortly, found that the degradation of emissions which can result is primarily due to the added hydrocarbons, but has often been incorrectly attributed to the ethanol.

The policy issues involved due to the methodological errors are significant. If states and other government entities, as well as fuel supply chain participants, use the model in its present form, they will mistakenly believe that ethanol’s emissions and pollutants are higher than reported in study after study over the past decade. The reported results will be just plain wrong. They will not even be half-truths, but zero truths. Distortions in decision making concerning the wisdom of alternative transitional replacement fuels, particularly ethanol, will occur and generate weaker ethanol markets and opportunities to build a strategic path to renewables. The EPA, rather than encourage use of the study and the model, should pull both back and suggest waiting until refereed review panels finish their work.

The nation is lucky to have Gina McCarthy as the head of the EPA. Her background is exquisite, her intellect is superior and her sensitivity to and understanding of the environmental issues facing America is second to none. She has been a fine EPA Administrator.

Then why am I worried when we have such a surfeit of riches in one individual leader? Long before McCarthy became Administrator, the EPA began working on a new set of guidelines governing the amount and use of ethanol in gasoline sold at the pump. The guidelines, more than likely, were ready in draft form simultaneously with Gina McCarthy’s appointment and the pressure to release them was intense, given earlier promises.

Because the positives and negatives of an increase or decrease in the RFS concerning ethanol use are imprecise, no real precise judgment can be made as to the final numbers, except the admonition, similar to the Hippocratic Oath: they do no harm and, do what the EPA suggests they probably will do, improve the economy, the environment and open fuel choices to the consumer. Sounds simple, but it isn’t! The EPA is considering modification of relatively recently determined RFS.

I understand the position of the oil companies to reduce what are effectively ethanol set asides. They have a financial stake in selling less corn-based ethanol with each gallon of gas, particularly when the content of ethanol rises to E85. Declining gas sales and prices make them eager to secure lower total annual ethanol requirements. Although the data is mixed, I also commiserate with the cattle growers who indicate they have had to pay, at times, higher prices for corn because of ethanol’s reliance on corn. Similarly, I am sensitive to environmentalists who worry that the acreage for corn-based ethanol is eating (excuse the pun) into conservation land and that total greenhouse gas emissions from production to use in vehicles of corn-based ethanol is not, generally, a good deal for the environment. I am not trying to be all things to all groups, but I am trying to weave my way through an intellectual and practical thicket.

The corn farmer’s advocacy of ethanol appears rational from an opportunity-cost standpoint. Corn-based ethanol seems, to them, to support higher prices for corn. They have done well in most recent years. While the facts remain unclear (credible researchers, such as those in the World Bank, have wavered over time on their position), the arguments made by groups and individuals concerned with what they believe is the relationship between corn-based ethanol and food supply should be debated fully. I, also, am inclined to believe those in the security business who feel that increased use of ethanol will reduce our dependency on important oil and lessen the nation’s need to fight wars in part to assure the world and the U.S. a share of global oil supply. Weaning ourselves from oil dependency is national need and priority.

It is tough to judge the efficacy of projections of ethanol sales, because of uncertain economic factors and the constraints put on consumer fuel choices by the oil industry’s almost-monopolistic restrictions at gas stations (just try buying safe, less costly alternative fuels at most gas stations) and federal regulations governing alternative fuel use as well as the sale of conversion kits. There is no free market for fuel.

Responding clearly to the conflicts over the value of corn-based ethanol and the annual total requirements for ethanol is not easy and should suggest the complexity of the involved issues and their presumed relationship to one another. Maybe increased use of corn stover and certainly natural gas-based ethanol for E85 would reduce food for fuel conflicts and lessen possible environmental problems. Nothing is perfect, but the production of ethanol using alternative feedstocks, such as stover and, hopefully soon, natural gas, could make a difference in providing better replacement fuels than just the use of corn based ethanol. Like a Talmudic scholar, I frequently, instead of counting sheep, find myself saying “on one hand, on the other hand” while trying to fall sleep. (I haven’t slept more than three full hours a night since Eisenhower was president.) I end up agreeing with the King in the King and I — “It’s a puzzlement!”

The EPA’s job is a tough one. Its lowering of the total amount of ethanol required to be used with gasoline may or may not have been the right decision. I know the EPA is considering modifying its initial estimates upward. We will have to wait and see what the Agency produces and then take part in a reasonable dialogue as to benefits and costs.

I am a somewhat more concerned about the basis used by the EPA to decide to lower ethanol requirements, at this point in time, than the new rules themselves. The rationale for the amended guidelines will become embedded in rulemaking and decisions could well generate unnecessary policy and constituent conflicts.

The Agency explained its recent decisions, in part, in terms of the absence of infrastructure and the possible harm that higher ethanol blends can do to vehicle engines. “EPA is proposing to adjust the applicable volumes of advanced biofuel and total renewable fuel to address projected availability of qualifying renewable fuels and limitations on the volume of ethanol that can be consumed in gasoline given practical constraints on the supply of higher ethanol blends to the vehicles that can use them and other limits on ethanol blend levels in gasoline (the ethanol blend wall).” Note that for the most part, the EPA does not dwell on environmental, economic or security issues in its basic rationale.

The EPA seems to mix supply and demand in a rather imprecise way. Ethanol is ethanol. Traditional infrastructure (e.g., pipelines) is not readily available now to transport ethanol from corn-based ethanol producers to blenders of gasoline and ethanol. But trains and heavy-duty vehicles are accessible and have provided reasonably efficient pipeline alternatives. Indeed, their availability, assuming modifications for safety concerns, particularly concerning trains, extends strategic options regarding the location of refineries/blenders and storage capacity to lessen leakage of environmentally harmful emissions.

The EPA’s argument for lowering ethanol requirements appears to rest, to a large degree, on a somewhat unconventional definition of supply. As one observer put it, the EPA’s regulations “muddle” the definition of supply with demand. There is an ample supply of ethanol now, indeed, a surplus. The EPA’s decision will likely increase the surplus or reduce the suppliers.

Demand for higher ethanol blends really has not been fairly tested in the analytical prelude to the recently changed regulations. Detroit and its dealers seem unwilling to clearly inform consumers of the government-approved use of blends higher than E15 in the flex-fuel cars that they are now producing and or are committed to producing in the future. Oil company franchise agreements limit replacement fuel pumps at their stations, often to off-center locations…somewhere near the men or women’s bathrooms, if at all. Correspondingly, the EPA’s regulations appear to mute the Agency’s own (and others) positive engine testing on E15 and its approval of E15 and E85 blends, within certain restrictions. Earlier, EPA studies were a bulwark against recent sustained attacks by the oil and, sometimes, the auto industry, as well as their friends on ethanol and its supposed negative affect on engines.

The EPA’s analysis of demand seems further blurred by the fact that if the Agency increased the supply of approved conversion kits, increased numbers of owners of existing vehicles would likely convert from gasoline to less-expensive ethanol-based fuels.

The EPA’s background rationale for the new RFS regulations understandably does not reflect the ability to produce ethanol from natural gas, a fuel in plentiful supply, and a natural gas to ethanol conversion process that may relatively soon be available. To do so would likely require an amendment to the RFS because natural gas is not a renewable fuel. The benefits include lower costs to the consumer, reduced import dependency and likely a decrease in pollutants and emissions. It appears a reasonable approach and provides a reasonable replacement fuel until renewable fuels are ready to compete for prime market time. Natural gas-based ethanol, as well as, as noted earlier, possible use of corn stover, would lessen the intensity of the food vs. fuel debate and the environmentalist concerns.

The EPA has tried hard to develop regulations that secure the public interest and appeal to varied constituencies. I respect its efforts. It’s a complicated task. I remember being asked by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to develop a report on simplifying its regulations for diverse programs. If I remember correctly, my report was over 600 pages long. Sufficiently said!