EPA’s ethanol ruling pleases no one

Nobody is happy with the EPA’s ruling on ethanol’s Renewable Fuel Standard made last week. The agency finally published its numbers after dodging the issue for two years and falling far behind on its legal obligations.

“It’s Christmas in May for Big Oil,” said Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa. “President Obama’s EPA continues to buy into Big Oil’s argument that the infrastructure isn’t in place to handle the fuel volume required by law. What happened to the president who claimed to support biofuels? He seems to have disappeared, to the detriment of consumers and our country’s fuel needs.”

Gov. Terry Branstad of Iowa, also a Republican, was not quite so negative. “We are disappointed that the EPA failed to follow the renewable volume levels set by Congress,” he said. “But we’re encouraged that the agency has provided some stability for producers by releasing a new RFS proposal, and made slight increases from their previous proposal.”

Even the question of whether the EPA’s new standard represents an increase or a decrease in the required amount of ethanol is under dispute. The original law, passed by Congress in 2007, specified that oil refiners were to absorb 14 billion gallons by 2013, 17 billion by 2014 and 19 billion this year. By 2013, however, it became obvious that the country would be unable to absorb 14 billion gallons without spilling over the “blend wall,” the standard of 10 percent ethanol that’s blended into virtually all gasoline in the U.S. There are concerns that some older vehicles can’t handle higher ethanol blends beyond E10 without sustaining damage to parts.

“By adopting the oil company narrative regarding the ability of the market to effectively distribute increasing volumes of renewable fuels, rather than putting the RFS back on track, the Agency has created its own slower, more costly, and ultimately diminished track for renewable fuels in this country,” Bob Dinneen, president and CEO of the Renewable Fuels Association, said in a statement.

The critics seem to have a point. Blends of E15 (up to 15 percent ethanol) and E85 are being sold across the country without any difficulties. Cars built since model year 2001 are approved to run on E15, and about one-third of automobiles are now flex-fuel, meaning they can tolerate any ethanol blend, up to E85. But the EPA has stuck with the “blend wall” in order to accommodate the oil refiners and automakers, who say they will not honor warranties on engines that might be damaged by ethanol.

The EPA standards announced last week are: 15.93 billion gallons for 2014 (that approximates actual sales for that year), 16.3 billion for 2015 and 17.4 billion for 2017. All these figures are about 5 billion gallons below the original statutory requirements. The last two have caused the most controversy. Ethanol supporters say the EPA is bound by the number in the 2007 law — even though there is a waiver provision. But critics who want to cut back on ethanol use argue that the figure is actually increasing from year to year and is only considered a reduction because it doesn’t match the original projections if 2007.

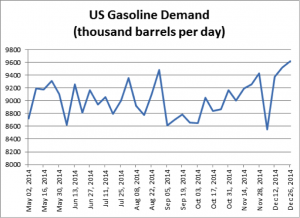

Really, it’s kind of ridiculous to think that Congress could predict exactly how much ethanol could be sold eight years hence. Typically, they made straight-line projections and assumed that gasoline consumption would hit 160 billion gallons per year by this time and keep going up. In fact, gasoline consumption started to drop almost the minute Congress passed the law, resulting from both improved fleet mileage and the reduction in driving that came with the recession. It now stands at 140 billion gallons. Had the law simply specified that ethanol consumption should be 10 percent of all gasoline consumption, there would be nothing to argue about.

The other place where the law is completely out of whack is in the mandates for non-corn ethanol made from cellulosic materials. At the time it was anticipated that cellulosic ethanol was right around the corner, and Congress specified that consumption should be 3.75 billion gallons in 2014, 7.2 billion gallons by 2017 and 21 billion gallons by 2022. In fact, the cellulosic-ethanol industry produced only 1.9 billion gallons in 2014 and has not increased much since. At one point, the EPA was actually fining oil refiners for not using a fuel that didn’t exist.

There’s little reason for either Congress or the EPA to be meddling in the ethanol market. Ethanol has established itself as an oxygenator and high-octane additive since the banning of MTBE. It would probably be added at a rate of around 10 percent, even without the mandates. E85 has a big price advantage over gasoline and would sell more if it were available. Last week, on the same day that the EPA published its new proposed Renewable Fuel Standard benchmarks, the Department of Agriculture pledged to match state funds for $100 million for the construction of new fueling stations designed to dispense E85. The fuel is very popular in the Midwest and would probably attract customers in other areas if it were easily accessible.

Finally, an export market for American corn ethanol is starting to take shape. Brazil mandates 35 percent of its fuel must be ethanol, but it has had problems with its sugar harvest and has started to import from the U.S. Europe is also getting big on ethanol and is looking across the Atlantic for new supplies.

Ethanol has proved its worth as a fuel additive and possibly as a gasoline substitute as well. All the sturm and drang over the EPA mandates have very little to do with the future of the industry.